Je l'avoue d'emblée: je ne suis pas un inconditionnel de Paul Halter. J'entends par là que si je me fais un devoir d'acheter et de lire chacun de ses nouveaux livres, je ne suis pas aussi enthousiaste que la plupart de ses nombreux admirateurs - et j'ai déjà explicité à plusieurs reprises les causes de mes réticences sans qu'il soit besoin que j'y revienne ici. Elles sont du reste sans importance dans le cas qui nous occupe.

Paul Halter fut longtemps un cas d'espèce dans le PPF (Paysage Polardier Francophone) au point que je le qualifiais de "singleton" dans ma critique, élogieuse d'ailleurs, de sa Toile de Pénélope. En effet, à rebours d'une production nationale largement vouée au noir le plus brut de décoffrage, Halter se spécialisait dans le roman d'énigme dans sa forme la plus radicale et la plus difficile, le crime impossible. Ses références n'étaient pas Jim Thompson et James Ellroy, mais Agatha Christie et surtout John Dickson Carr. Indifférent aux modes, il suivait son chemin de petit bonhomme, soutenu par un lectorat fidèle et hébergé par l'éditeur historique de ses modèles, Le Masque, dont il était l'un des auteurs-vedettes. Alors oui bien sûr, l'establishment le regardait au mieux avec condescendance et au pire avec mépris, et il ne fut jamais finaliste d'aucun Grand Prix de Littérature Policière ou Trophée 813, mais cela ne l'empêcha pas de publier, impavide, son ou ses romans annuels pendant près d'un quart de siècle.

Et puis vint la catastrophe. Le Masque fut racheté par les Editions Jean-Claude Lattès et confié à une dame dont le roman d'énigme n'était pas vraiment la tasse de thé et qui ambitionnait de faire de la maison un Rivages bis (comme si le premier ne suffisait pas...) Adieu donc la collection jaune au profit du grand format, et les auteurs "classiques" furent priés d'aller se faire voir ailleurs. Bonnes ventes obligent, Halter eut droit à un sursis mais les choses se gâtèrent rapidement et les nouveautés devinrent de plus en plus rares, jusqu'à ce Voyageur du passé qui marqua le divorce. Halter publie depuis en auto-édition.

L'ironie grinçante de cette histoire c'est qu'au moment où l'édition française lui tournait le dos, Halter avait enfin réussi à faire une (petite, mais certaine) percée sur le marché anglophone grâce aux efforts de l'infatigable John Pugmire. Ses livres étaient traduits en anglais et ses nouvelles paraissaient désormais en exclusivité dans le Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine dont il est pratiquement devenu LE "French writer". L'exploit est d'autant plus remarquable que, comme beaucoup le savent mais peu l'avouent, les trois-quarts de la production polardière nationale sont inexportables - les quelques exceptions étant généralement honnies du milieu parce que trop "commerciales" - et devrait susciter un regain d'intérêt ici.

Il n'en est rien, bien entendu. Et c'est honteux.

A l'heure où le polar français retrouve enfin la diversité qui était la sienne avant le déferlement du regrettable "néo-polar" il serait bon que Halter retrouve enfin sa place dans le PPF, d'abord parce qu'il le mérite, ensuite parce qu'il est à ce jour le dernier représentant en France d'un genre où notre pays a autrefois brillé et où il pourrait briller encore si les éditeurs et les critiques faisaient preuve d'un poil plus d'ouverture d'esprit (le public est déjà acquis, les auteurs qui se vendent vraiment le prouvent) Le Masque - qui a depuis changé de barreur - renoue lentement avec ses racines, peut-être une réconciliation serait-elle possible? Vous pouvez me traiter de rêveur, mais je ne suis pas le seul - du moins je l'espère.

30/04/2018

28/04/2018

Mary, Jacques et Melville

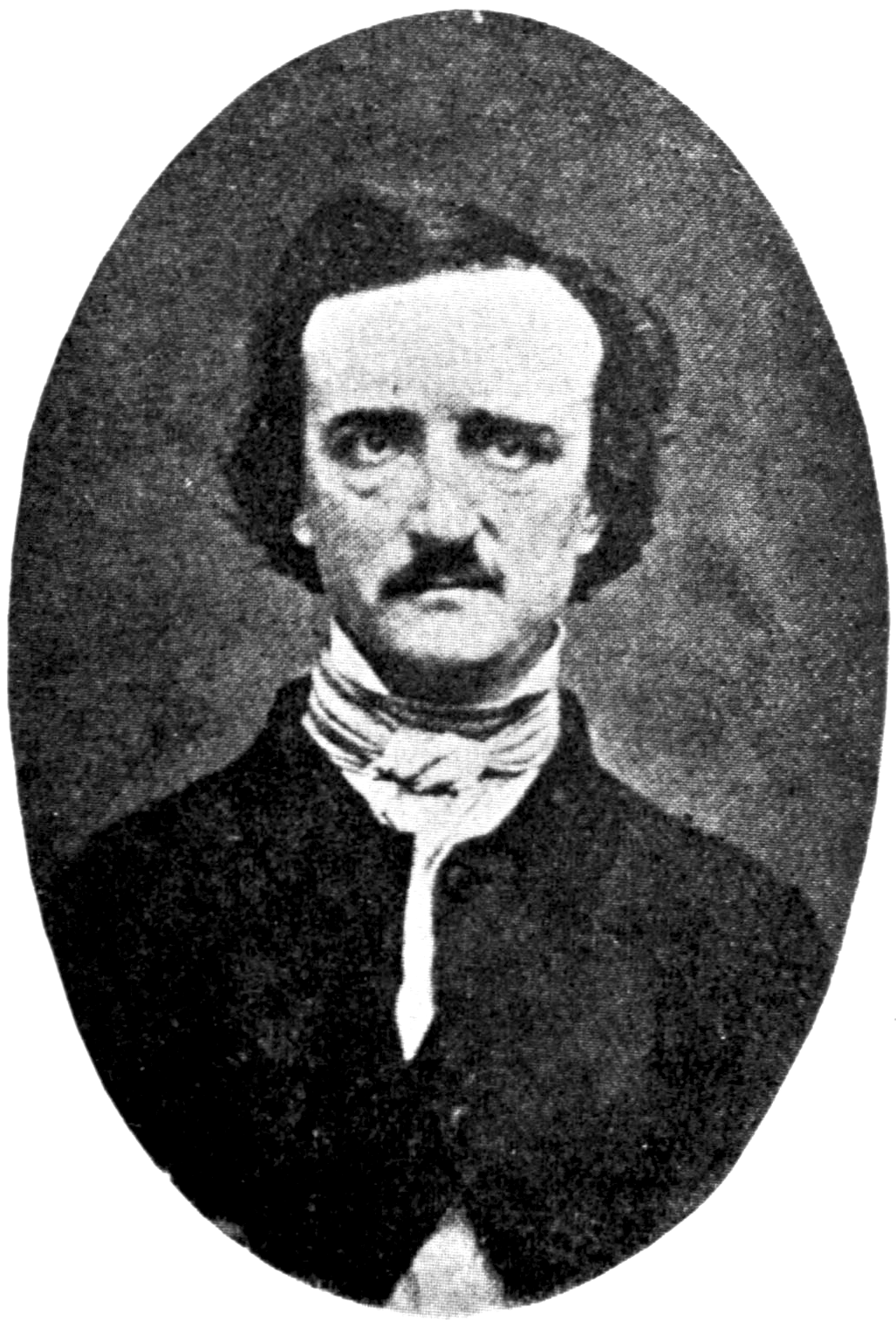

C'est un fait entendu sauf de quelques contrariens, tous français comme par hasard: la littérature criminelle moderne naquit aux Etats-Unis en 1841 quand un certain Edgar A. Poe publia une nouvelle intitulée Double assassinat dans la rue Morgue dans le Graham's Magazine. Poe, surpris par le succès de cette historiette mais pas homme à laisser perdre une bonne idée, enchaîna avec deux autres enquêtes du Chevalier Dupin puis passa à autre chose. La graine étant plantée, et solidement plantée, on pouvait s'attendre à voir une belle plante émerger. Il n'en fut rien, du moins en terre américaine. Le gros de la floraison se fit ailleurs, en France puis en Grande-Bretagne.

Honneur aux dames, commençons avec Mary Roberts Rinehart, qui est peut-être le membre le plus important de notre trio, par sa production et par son héritage. Bien qu'un grand nombre de ses livres aient été publiés chez nous et ce dès 1910, Rinehart reste mal connue en France, dans le sens double qu'elle n'est connue que de quelques amateurs et, souvent, pour de mauvaises raisons. C'est en effet à Rinehart que l'on attribue la maternité du genre dit Had-I-But-Known (HIBK, "Si j'avais su") une forme de suspense destiné en priorité à un public féminin et mettant le plus souvent aux prises une jeune femme contre d'obscures menaces dont la tirera in extremis le bras musculeux de quelque beau ténébreux. Ce genre, beaucoup plus riche et intéressant qu'il n'y paraît de prime abord, a toujours eu mauvaise presse auprès de la critique et Rinehart en tant que première "responsable" eut longtemps droit à ses quolibets. C'est doublement injuste car d'une part Rinehart est loin d'être aussi "guimauve" que ses héritières putatives, et de l'autre sa contribution à la formation d'une littérature policière nationale est indubitable. A contre-courant de ses collègues, Rinehart ne cherche pas à imiter les Anglais, ni au niveau du style ni au niveau des intrigues. On ne trouve pas chez elle de grand détective et le chemin vers la vérité n'est pas un simple jeu de pistes. Surtout, l'accent est mis sur les gens, les personnes impliquées dans le crime et qui sont chez elles les véritables protagonistes au lieu de simples accessoires qu'ils sont chez d'autres. La question centrale devient non pas, Qui a tué? mais Vont-ils s'en sortir? Eh oui braves gens, trente ans avant Cornell Woolrich, Mary a inventé le suspense. Ce n'est pas la seule de ses innovations. Rinehart s'exprime dans un idiome beaucoup plus relâché que ses collègues anglais, le but étant d'abolir la distance entre le lecteur et le narrateur (qui est souvent une narratrice) et on trouve chez elle pour la première fois ce ton direct, sans fioriture, qui est pour beaucoup la marque du polar américain. Enfin, ses intrigues souvent labyrinthiques - les critiques orthodoxes le lui reprochèrent d'ailleurs - rompent avec le schéma crime-enquête-solution hérité de Poe et raffiné par les Anglais. Le héros prend des risques, et parfois des coups. Le roman noir se souviendra de la leçon, sans bien sûr renvoyer l'ascenseur. Un siècle après la parution de L'Escalier en colimaçon, il est intéressant et délicieusement ironique de constater que la progéniture de Rinehart comprend les trois quarts de la production policière américaine et même mondiale; tout le monde lui doit quelque chose, ce qui n'est pas mal du tout pour un auteur que la critique ne cessa de dénoncer pour sa superficialité et ses facilités...

Honneur aux dames, commençons avec Mary Roberts Rinehart, qui est peut-être le membre le plus important de notre trio, par sa production et par son héritage. Bien qu'un grand nombre de ses livres aient été publiés chez nous et ce dès 1910, Rinehart reste mal connue en France, dans le sens double qu'elle n'est connue que de quelques amateurs et, souvent, pour de mauvaises raisons. C'est en effet à Rinehart que l'on attribue la maternité du genre dit Had-I-But-Known (HIBK, "Si j'avais su") une forme de suspense destiné en priorité à un public féminin et mettant le plus souvent aux prises une jeune femme contre d'obscures menaces dont la tirera in extremis le bras musculeux de quelque beau ténébreux. Ce genre, beaucoup plus riche et intéressant qu'il n'y paraît de prime abord, a toujours eu mauvaise presse auprès de la critique et Rinehart en tant que première "responsable" eut longtemps droit à ses quolibets. C'est doublement injuste car d'une part Rinehart est loin d'être aussi "guimauve" que ses héritières putatives, et de l'autre sa contribution à la formation d'une littérature policière nationale est indubitable. A contre-courant de ses collègues, Rinehart ne cherche pas à imiter les Anglais, ni au niveau du style ni au niveau des intrigues. On ne trouve pas chez elle de grand détective et le chemin vers la vérité n'est pas un simple jeu de pistes. Surtout, l'accent est mis sur les gens, les personnes impliquées dans le crime et qui sont chez elles les véritables protagonistes au lieu de simples accessoires qu'ils sont chez d'autres. La question centrale devient non pas, Qui a tué? mais Vont-ils s'en sortir? Eh oui braves gens, trente ans avant Cornell Woolrich, Mary a inventé le suspense. Ce n'est pas la seule de ses innovations. Rinehart s'exprime dans un idiome beaucoup plus relâché que ses collègues anglais, le but étant d'abolir la distance entre le lecteur et le narrateur (qui est souvent une narratrice) et on trouve chez elle pour la première fois ce ton direct, sans fioriture, qui est pour beaucoup la marque du polar américain. Enfin, ses intrigues souvent labyrinthiques - les critiques orthodoxes le lui reprochèrent d'ailleurs - rompent avec le schéma crime-enquête-solution hérité de Poe et raffiné par les Anglais. Le héros prend des risques, et parfois des coups. Le roman noir se souviendra de la leçon, sans bien sûr renvoyer l'ascenseur. Un siècle après la parution de L'Escalier en colimaçon, il est intéressant et délicieusement ironique de constater que la progéniture de Rinehart comprend les trois quarts de la production policière américaine et même mondiale; tout le monde lui doit quelque chose, ce qui n'est pas mal du tout pour un auteur que la critique ne cessa de dénoncer pour sa superficialité et ses facilités...

Notre second hôte est plus classique dans la forme, mais son influence est tout aussi déterminante à sa manière. Jacques Futrelle est paradoxalement le plus connu et apprécié des amateurs français grâce aux efforts de Roland Lacourbe, et sans doute celui qui se lit le plus facilement et avec le plus de plaisir aujourd'hui. Sa mort à bord du Titanic est l'une des grandes tragédies de l'histoire de la littérature policière. C'est que la grande force de Futrelle, c'est qu'il est moderne. Si Rinehart anticipe le suspense psychologique et le roman noir, Futrelle annonce lui le roman d'énigme triomphant de l'entre-deux-guerres et s'il opère à première vue en terrain familier - le grand détective qui résout les énigmes les plus tortueuses - il le fait d'une manière qui n'appartient qu'à lui. Son héros, S.F.X. Van Dusen (La Machine à penser pour les intimes) n'intervient pratiquement que sur des cas-limites, souvent des crimes impossibles. A l'heure où le roman-détective cherche à susciter l'admiration pour les prouesses intellectuelles du détective, Futrelle cherche à surprendre et à épater. Chez lui les maisons disparaissent, les voitures aussi, les assassins traversent les murs et ne laissent pas d'empreintes dans la neige... Ce goût du tour de force associé à un mépris souverain pour le réalisme est une caractéristique spécifique du whodunit "à l'américaine" et se retrouvera par la suite chez Ellery Queen, Fredric Brown et surtout John Dickson Carr dont Futrelle est en quelque sorte l'annonciateur. Journaliste, Futrelle écrit comme Rinehart dans une langue simple, quoique non dénuée d'humour. Et il n'hésite pas à expérimenter à l'occasion, là aussi avec des décennies d'avance sur les autres (sa nouvelle The Mystery of Room 666 anticipe un célèbre roman d'Agatha Christie paru vingt-cinq ans plus tard...)

Notre second hôte est plus classique dans la forme, mais son influence est tout aussi déterminante à sa manière. Jacques Futrelle est paradoxalement le plus connu et apprécié des amateurs français grâce aux efforts de Roland Lacourbe, et sans doute celui qui se lit le plus facilement et avec le plus de plaisir aujourd'hui. Sa mort à bord du Titanic est l'une des grandes tragédies de l'histoire de la littérature policière. C'est que la grande force de Futrelle, c'est qu'il est moderne. Si Rinehart anticipe le suspense psychologique et le roman noir, Futrelle annonce lui le roman d'énigme triomphant de l'entre-deux-guerres et s'il opère à première vue en terrain familier - le grand détective qui résout les énigmes les plus tortueuses - il le fait d'une manière qui n'appartient qu'à lui. Son héros, S.F.X. Van Dusen (La Machine à penser pour les intimes) n'intervient pratiquement que sur des cas-limites, souvent des crimes impossibles. A l'heure où le roman-détective cherche à susciter l'admiration pour les prouesses intellectuelles du détective, Futrelle cherche à surprendre et à épater. Chez lui les maisons disparaissent, les voitures aussi, les assassins traversent les murs et ne laissent pas d'empreintes dans la neige... Ce goût du tour de force associé à un mépris souverain pour le réalisme est une caractéristique spécifique du whodunit "à l'américaine" et se retrouvera par la suite chez Ellery Queen, Fredric Brown et surtout John Dickson Carr dont Futrelle est en quelque sorte l'annonciateur. Journaliste, Futrelle écrit comme Rinehart dans une langue simple, quoique non dénuée d'humour. Et il n'hésite pas à expérimenter à l'occasion, là aussi avec des décennies d'avance sur les autres (sa nouvelle The Mystery of Room 666 anticipe un célèbre roman d'Agatha Christie paru vingt-cinq ans plus tard...)

Non que les auteurs américains fussent complètement inactifs. De jolis bourgeons apparaissaient de temps à autre, généralement sans lendemain, tels que le Out of His Head de Thomas Bailey Aldrich, The Dead Letter de Seeley Regester (probablement le premier roman policier écrit par une femme) mais il faut attendre 1878 et la parution du Crime de la Cinquième Avenue de Anna Katharine Green pour voir apparaître le premier auteur spécialisé et dont l'audience et l'influence dépassent les frontières du pays. Même ainsi la littérature policière américaine reste à la traîne jusqu'à la fin du siècle, incapable qu'elle est de se dépétrer des influences contraires du Dime Novel et de l'école anglaise représentée par Conan Doyle et son Sherlock Holmes.

Les choses commencent à se débloquer dans la première décennie du XXème siècle, avec l'émergence d'un quintet d'auteurs qui, chacun à sa manière, va contribuer à doter le roman criminel local d'une identité propre. Deux d'entre eux, Arthur B. Reeve et Carolyn Wells, n'ont été que peu ou pas traduits en français et je ne m'appesantirai donc pas sur eux dans la mesure où je souhaite m'en tenir à des auteurs et des oeuvres que le lecteur francophone puisse juger sur pièces. Leur influence fut du reste limitée dans le temps et dans la postérité. Il en va tout autrement des trois autres.

Honneur aux dames, commençons avec Mary Roberts Rinehart, qui est peut-être le membre le plus important de notre trio, par sa production et par son héritage. Bien qu'un grand nombre de ses livres aient été publiés chez nous et ce dès 1910, Rinehart reste mal connue en France, dans le sens double qu'elle n'est connue que de quelques amateurs et, souvent, pour de mauvaises raisons. C'est en effet à Rinehart que l'on attribue la maternité du genre dit Had-I-But-Known (HIBK, "Si j'avais su") une forme de suspense destiné en priorité à un public féminin et mettant le plus souvent aux prises une jeune femme contre d'obscures menaces dont la tirera in extremis le bras musculeux de quelque beau ténébreux. Ce genre, beaucoup plus riche et intéressant qu'il n'y paraît de prime abord, a toujours eu mauvaise presse auprès de la critique et Rinehart en tant que première "responsable" eut longtemps droit à ses quolibets. C'est doublement injuste car d'une part Rinehart est loin d'être aussi "guimauve" que ses héritières putatives, et de l'autre sa contribution à la formation d'une littérature policière nationale est indubitable. A contre-courant de ses collègues, Rinehart ne cherche pas à imiter les Anglais, ni au niveau du style ni au niveau des intrigues. On ne trouve pas chez elle de grand détective et le chemin vers la vérité n'est pas un simple jeu de pistes. Surtout, l'accent est mis sur les gens, les personnes impliquées dans le crime et qui sont chez elles les véritables protagonistes au lieu de simples accessoires qu'ils sont chez d'autres. La question centrale devient non pas, Qui a tué? mais Vont-ils s'en sortir? Eh oui braves gens, trente ans avant Cornell Woolrich, Mary a inventé le suspense. Ce n'est pas la seule de ses innovations. Rinehart s'exprime dans un idiome beaucoup plus relâché que ses collègues anglais, le but étant d'abolir la distance entre le lecteur et le narrateur (qui est souvent une narratrice) et on trouve chez elle pour la première fois ce ton direct, sans fioriture, qui est pour beaucoup la marque du polar américain. Enfin, ses intrigues souvent labyrinthiques - les critiques orthodoxes le lui reprochèrent d'ailleurs - rompent avec le schéma crime-enquête-solution hérité de Poe et raffiné par les Anglais. Le héros prend des risques, et parfois des coups. Le roman noir se souviendra de la leçon, sans bien sûr renvoyer l'ascenseur. Un siècle après la parution de L'Escalier en colimaçon, il est intéressant et délicieusement ironique de constater que la progéniture de Rinehart comprend les trois quarts de la production policière américaine et même mondiale; tout le monde lui doit quelque chose, ce qui n'est pas mal du tout pour un auteur que la critique ne cessa de dénoncer pour sa superficialité et ses facilités...

Honneur aux dames, commençons avec Mary Roberts Rinehart, qui est peut-être le membre le plus important de notre trio, par sa production et par son héritage. Bien qu'un grand nombre de ses livres aient été publiés chez nous et ce dès 1910, Rinehart reste mal connue en France, dans le sens double qu'elle n'est connue que de quelques amateurs et, souvent, pour de mauvaises raisons. C'est en effet à Rinehart que l'on attribue la maternité du genre dit Had-I-But-Known (HIBK, "Si j'avais su") une forme de suspense destiné en priorité à un public féminin et mettant le plus souvent aux prises une jeune femme contre d'obscures menaces dont la tirera in extremis le bras musculeux de quelque beau ténébreux. Ce genre, beaucoup plus riche et intéressant qu'il n'y paraît de prime abord, a toujours eu mauvaise presse auprès de la critique et Rinehart en tant que première "responsable" eut longtemps droit à ses quolibets. C'est doublement injuste car d'une part Rinehart est loin d'être aussi "guimauve" que ses héritières putatives, et de l'autre sa contribution à la formation d'une littérature policière nationale est indubitable. A contre-courant de ses collègues, Rinehart ne cherche pas à imiter les Anglais, ni au niveau du style ni au niveau des intrigues. On ne trouve pas chez elle de grand détective et le chemin vers la vérité n'est pas un simple jeu de pistes. Surtout, l'accent est mis sur les gens, les personnes impliquées dans le crime et qui sont chez elles les véritables protagonistes au lieu de simples accessoires qu'ils sont chez d'autres. La question centrale devient non pas, Qui a tué? mais Vont-ils s'en sortir? Eh oui braves gens, trente ans avant Cornell Woolrich, Mary a inventé le suspense. Ce n'est pas la seule de ses innovations. Rinehart s'exprime dans un idiome beaucoup plus relâché que ses collègues anglais, le but étant d'abolir la distance entre le lecteur et le narrateur (qui est souvent une narratrice) et on trouve chez elle pour la première fois ce ton direct, sans fioriture, qui est pour beaucoup la marque du polar américain. Enfin, ses intrigues souvent labyrinthiques - les critiques orthodoxes le lui reprochèrent d'ailleurs - rompent avec le schéma crime-enquête-solution hérité de Poe et raffiné par les Anglais. Le héros prend des risques, et parfois des coups. Le roman noir se souviendra de la leçon, sans bien sûr renvoyer l'ascenseur. Un siècle après la parution de L'Escalier en colimaçon, il est intéressant et délicieusement ironique de constater que la progéniture de Rinehart comprend les trois quarts de la production policière américaine et même mondiale; tout le monde lui doit quelque chose, ce qui n'est pas mal du tout pour un auteur que la critique ne cessa de dénoncer pour sa superficialité et ses facilités...

Terminons avec celui qui est sans doute le moins connu du public français puisqu'il a fallu attendre 2014 pour que son magnum opus soit publié chez nous grâce à l'excellent Jean-Daniel Brèque, hélas dans l'indifférence générale. Melville Davisson Post, puisque c'est lui, est en quelque sorte le patriarche du lot, puisqu'il commence à écrire à la fin du XIXème siècle. Il est aussi le moins "moderne" et ne se rattache à aucune école connue; c'est pourtant un auteur capital et précisément pour cette raison. Il se distingue une première fois en créant un mémorable personnage d'avocat marron, Randolph Mason (Perry lui doit son nom de famille) qui a pour particularité de ne défendre que des accusés coupables et de trouver chaque fois un moyen légal de les tirer d'affaire. Post, qui était lui-même avocat, parlait de ce qu'il connaissait et contribua à faire changer plusieurs lois par ses écrits. Mais c'est à un personnage tout à fait différent qu'il devra sa notoriété et sa place au panthéon des auteurs de romans policiers américains. L'Oncle Abner, puisque c'est lui, évolue dans la Virginie post-coloniale et, armé de sa Bible et de son solide bon sens, démasque les serpents qui grouillent dans son "jardin d'Eden". Outre que Post invente ainsi le polar historique, il crée aussi par la même occasion le premier détective authentiquement américain en ce sens qu'il ne peut exister nulle part ailleurs. Abner peut également être considéré comme une réponse américaine au Père Brown de Chesterton par le caractère "sacré" qu'ils attribuent tous deux à leur "vocation" de détective, même si leurs théologies respectives sont tout à fait différentes. Le statut de Grand Détective de l'Oncle Abner tient davantage à sa forte personnalité qu'aux affaires qu'il débrouille, même si certaines sont très astucieuses. Post n'est en effet pas un virtuose de l'intrigue, étant avant tout un "littéraire" qui soigne son style et consacre une grande attention à ses personnages et à l'évocation du pays où ils évoluent. C'est sans doute le premier auteur américain de fiction criminelle qui entretienne avec son sol un lien aussi puissant, et qui en parle, contrairement à ses collègues plus urbains. Sa postérité se trouve dans ce que l'on pourrait appeler le polar américain "régionaliste", de Phoebe Atwood Taylor à (eh oui) James Lee Burke.

Si ce billet plus long que d'habitude vous a donné envie de vous plonger dans les oeuvres de ces trois auteurs disponibles en français et, pour ceux qui parlent la langue du Barde, de poursuivre avec celles encore inédites; si, surtout, il donne des idées à un ou des éventuels éditeurs qui passeraient par là (je suis d'un naturel optimiste) alors le plaisir que j'ai eu à l'écrire se doublera de celui d'avoir été utile.

Time for Questions

While the current GAD revival undoubtedly rejoices me, I think some questions about it need to be raised if we want it to last and be viable.

First is, why is it occurring NOW? Contemporary crime fiction, at least the one that we're supposed to take seriously, is going noir full speed and the other subgenres are increasingly marginalized. So why are century-old, definitely non-edgy and non-gritty mysteries popular again?

Second, will it last? Is it a brief fashion craze like rockabilly was in the early 80s (remember the Stray Cats) or is GAD back to stay? I certainly hope for the latter but cannot exclude the former.

Third, can it spread? As one of this blog's faithful commenters pointed out, the revival is as of now largely a British affair thanks to the efforts of Martin Edwards and Tony Medawar and some courageous independent publishers like Dean Street Press or Blackheath. America is way behind and France, well, is France. I understand that Britain is closely associated with the Golden Age in most people's minds, but we all know that it is a cliché and one that had, and still has, nefarious editorial consequences.

Fourth and final, can it influence modern crime fiction? Unlike what most people think I don't particularly "dig" reading old books from the time before I was born; it's just that they're the only ones satisfying my needs as a reader. I'd just as much like to read more contemporary fare; the problem is, most of what is published these days is the kind of crime fiction that I don't like and critics and awards make repeatedly clear that they don't give a fig what I'm thinking and the few writers I like are not worthy. I'd be glad thus if the current GAD revival could bring out a new generation of mystery writers who really care about the mystery element of their work. We have seen some encouraging signs with the runaway successes of Magpie Murders and The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle but we're still a long way from a traditionalist mystery winning the Edgar.

These are for now the lines I'm thinking along. Your own answers are welcome.

19/04/2018

Le Boucher

This post is not a review, however, but rather a kind of a tribute. Boucher died 50 years ago and it's safe to say that we're not burdened with commemorations - that short memory, still and always. This pains me a lot, as I've always regarded him as some kind of a patron saint, not just because Marvin Lachman kindly but undeservingly named me as one of his (potential) heirs but because we have a lot in common, not the less our very catholic (pun intended) tastes when it comes to crime fiction, though he was admittedly more tolerant of noir that I am. Also, I think Boucher is still relevant today as unlike some of his fellow critics he has more often been proved right than wrong.

Let's go back to Jeffrey Marks's book. One of its most interesting features is an appendix listing Boucher's favorite crime novels by year during his run at The New York Times. You'd expect some or most of the items to be now obscure and forgotten as is frequently the case with such lists - tastes and fashions are constantly evolving, and some works pass the test of time and others don't - but it's exactly the opposite. Bona fide or should-be classics, some of them not evident at the time, are the norm and most of the names are familiar to the seasoned reader. Of course there's room for discussion of why this book and not another, and Boucher at times let friendship get in the way of clear-eyed criticism (No modern John Dickson Carr fan including me would dare to claim that The Skeleton in the Clock or (gasp!) Scandal at High Chimneys were among their respective years's, or any other for that matter, best) but overall the guy recognized a great book when he met one, whatever its genre.

The latter point is where I think Boucher's relevance to modern criticism lies. If you were kind and patient enough to follow me over this blog's decade of existence you know that critics are one of my many pet peeves. All too often they display little or no knowledge of the history of the genre, regard plot as perfunctory and reduce crime fiction to what they perceive as its "grittiest", "edgiest" forms: thrillers, hardboiled and above all noir. Also, they expect a good crime novel to do more than "just" entertain; it must "say something" about society, politics, gender, race, religion and what have you - in short, a good crime novel is a

literary novel with a criminal slant. Such a book is said to "transcend the genre" which seem to be the highest praise you can give to a crime novel these days. As a result, lots of professional crime fiction reviews read like articles straight from the NYRB with every aspect of the book dissected but the distinctive features that make it - more or less - a mystery. Awards follow suit of course and needless to say, cosies and "entertainers" need no apply.

While a progressive in his tastes and always on the prowl for something different, Boucher never forgot that crime fiction like any genre exists primarily to entertain; he never looked down on those books that didn't try to "transcend" anything - and I think he'd have loathed the term and its implications as much as I do. Also, he remained loyal all his life to the traditional mystery with its great detectives, clever plotting and fair-play clueing, and all his "Best of the Year" list include at least one specimen of the species - and here may be what differentiates most Boucher from most of his so-called heirs: He was, first and foremost, a fan, not just some folk that read mysteries for some reason other than that they're mysteries.

If it is to survive as an independent form rather than an annex of literary fiction, the mystery genre must become a fan-driven genre again, both in the writing and reading departments. We definitely need more Bouchers and less - well, write here the name of a critic you particularly abbhor.

02/04/2018

Steven Bochco

This entry is bilingual. Please scroll down for the English-language version.

Je me souviendrai avant tout de Steven Bochco comme l'auteur de l'un des meilleurs épisodes de Columbo, "Le Livre témoin" (réalisé par un autre Steven, un certain Spielberg qui a lui aussi fait une petite carrière me dit-on) et le co-créateur de deux séries que j'ai beaucoup aimées dans ma lointaine jeunesse, "La Loi de Los Angeles" - il emporte avec lui le secret du papillon de Vénus, les fans comprendront - et "Docteur Doogie" dont je dois être le seul à me souvenir vu que j'étais déjà pratiquement le seul à regarder à l'époque.

Je suis plus réservé quant à son apport à la fiction policière et, au delà, au développement des séries télévisées depuis une quarantaine d'années. "Hill Street Blues" n'eut d'autre effet sur moi que de me convaincre que le métier de policier est dans la vraie vie d'un ennui mortel, et "NYPD Blue" contribua à démocratiser la figure honnie du "flic à problème" qui a depuis fait les beaux jours de la littérature, du cinéma et de la télévision en panne d'idée. Surtout, je lui reproche ce que dont les autres le félicitent, à savoir d'avoir imposé la série "feuilletonnante". Pour ses laudateurs, il a ainsi apporté plus de profondeur aux intrigues et aux personnages; pour moi il a surtout importé les recettes du soap-opera et du serial dans un format qui s'était construit contre ces derniers.

On l'oublie trop souvent, mais les premières "grandes" séries - grandes en termes de qualité - étaient pour la plupart des anthologies: Alfred Hitchcock Présente, La Quatrième Dimension, Au-delà du réel, Playhouse 90, Thriller et j'en passe. Des histoires bouclées sur elles-mêmes avec des protagonistes différents chaque semaine. Bref, de véritables court-métrages, souvent réalisés comme des longs. Même les séries à personnages récurrents fonctionnaient sur ce mode. Il faut dire au crédit de Bochco que ce format commença de s'essouffler dans les années soixante et soixante-dix, l'écriture et l'esthétique ne suivant plus. Et certaines séries feuilletonnantes sont tout à fait remarquables, je pense notamment à St. Elsewhere que je considère comme la plus grande série de tous les temps (vous ne connaissez pas? remerciez la télévision française) Mais le ver étant dans le fruit, le feuilleton a fini par avaler son hôte de sorte que la grande majorité des séries célébrées aujourd'hui, surtout celles du câbles, sont en fait des feuilletons dont les épisodes n'existent plus individuellement et les intrigues se traînent sur des saisons entières. Je trouve d'ailleurs suprêmement ironique de voir des gens qui trouvent Les Feux de l'Amour ringards s'extasier devant... non, je ne donnerai pas de nom.

Mais bon, ne mégotons pas à Steven Bochco sa place dans l'histoire du Huitième Art. Elle est colossale et incontournable.

I'll remember Steven Bochco first and foremost as the guy who wrote one of the best episodes of Columbo, "Murder by the Book", that also happened to be directed by another Steven, one named Spielberg who went on to enjoy some success too. I'll also remember him as the (co-) creator of two shows that I liked as a teenager, "L.A. Law" (now we'll never know about the Venus Butterfly) and "Doogie Howser M.D.", which I'm sure to be the only one in France to remember, since I was probably the only one watching it.

This blog, however, is about crime fiction and I have to say I'm more than reserved about Bochco's contribution to the genre, at least in its TV incarnation. The only effect "Hill Street Blues" had on yours truly was to convince me that real-life police is one of the most boring jobs in the world; "NYPD Blue" on the other hand introduced to the small screen one of the most tiresome trends in contemporary crime fiction, The Troubled Cop. My biggest beef, however, is precisely what fans and critics laud him for, the serialization of TV shows. Said fans and critics say by doing that he gave more depth to the form, especially as pertains to characters, whereas I say he basically brought the time-worn recipes of soap-operas and old-time serials to a form that was precisely created as a reaction against them.

People tend to forget that as they think there is only one Golden Age of Television that began with the first episode of The Sopranos, but the first great TV shows - great in terms of quality - were anthologies: Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, Playhouse 90, Thriller... Self-contained stories with a different cast each week. Even shows with recurring characters followed the same model. As years went by, however, the form wore thin as both writing and filmmaking declined, and was certainly in need of a renewal. Also serialization gave us some wonderful shows such as St. Elsewhere which I still regard as the best American TV show ever made. The problem is, the serial element ended phagocytosing the whole so that most of the current "prestige" shows are actually serials with insecable episodes and plots and subplots running over whole seasons. I find extremely ironic that people who laugh at The Bold and The Beautiful's corny long-windedness gush over - no, I won't give any name, there are too many candidates.

Still, let us no more speaking ill of the dead, especially one with so impressive a resume. Steven Bochco's place in the Television Hall of Fame is well deserved and secure; but a little critical perspective is never useless.

15/03/2018

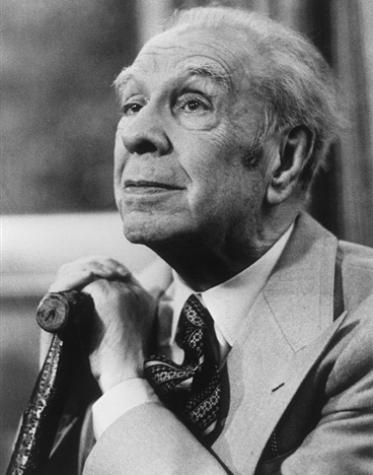

The Indispensable Edgar

It's always heartening to find oneself in agreement with a genius, though said genius on another hand may find it depressing depending on how bright one are. I hope Jorge Luis Borges wouldn't be too ashamed to be associated with yours truly. But I digress; let's get straight to the point.

Borges was famously a fan of detective fiction (I stress "detective" as other forms of crime fiction didn't seem to appeal to him as much) and it was thus inevitable that he addresses the subject in one of his conferences, which he did. Sadly the text doesn't appear to be available in English (though it is in French) and the content is too meaty for an extensive summary here; I may come back to it in future posts. What concerns us here is what he says about the putative father of the genre, Edgar Allan Poe. Borges credits him with being one of only two writers, both American as it happens, without which modern literature as we know it wouldn't exist and also for inventing a new kind of reader, one that doesn't take what the author says at face value. Borges then proceeds to show what such a reader would make of the famous opening of Don Quixote which admittedly allows itself particularly well to such a reading. The first point, however, is of particular interest as it is the one in which I have been in agreement with Borges even before I read him.

English-speaking readers and critics, especially American ones, are often skeptical of Poe's literary value and bemused at his continued popularity, ascribing it either to the sensational and thus appealing nature of his work or to improvement in translation. Rarely do they take him seriously as a founding figure of American literature; they rather grant that status to the more literarily respectable Hawthorne or Melville.

And yet Poe, as Borges saw, is indispensable in a way that neither Nathaniel or Herman are. The influence of both writers, and I'm saying that as a fan of the former*, is mostly limited to North American literature. Poe on the other hand is a global phenomenon, his heirs are to be found all over the world and many of them were major players in their own right. Strike him out and suddenly there is no Baudelaire, Stevenson, Dostoyevsky, Verne and of course Borges - to name just a few - at least as we know them. He is also responsible, directly or indirectly, for the existence of genres that didn't or barely existed before him - crime fiction of course, but also science-fiction, horror and even adventure in its modern sense. Finally, he contributed to the rise of the tale or short story as a viable and legitimate form of fiction. Now it doesn't necessarily make him a writer of Hawthorne's or Melville's caliber on purely literary grounds (I think it does, but I'm open to discussion) but his legacy is far more important and enduring.

Not bad for a guy who died at 40 in abject poverty and near obscurity.

|

| Jorge Luis Borges |

English-speaking readers and critics, especially American ones, are often skeptical of Poe's literary value and bemused at his continued popularity, ascribing it either to the sensational and thus appealing nature of his work or to improvement in translation. Rarely do they take him seriously as a founding figure of American literature; they rather grant that status to the more literarily respectable Hawthorne or Melville.

And yet Poe, as Borges saw, is indispensable in a way that neither Nathaniel or Herman are. The influence of both writers, and I'm saying that as a fan of the former*, is mostly limited to North American literature. Poe on the other hand is a global phenomenon, his heirs are to be found all over the world and many of them were major players in their own right. Strike him out and suddenly there is no Baudelaire, Stevenson, Dostoyevsky, Verne and of course Borges - to name just a few - at least as we know them. He is also responsible, directly or indirectly, for the existence of genres that didn't or barely existed before him - crime fiction of course, but also science-fiction, horror and even adventure in its modern sense. Finally, he contributed to the rise of the tale or short story as a viable and legitimate form of fiction. Now it doesn't necessarily make him a writer of Hawthorne's or Melville's caliber on purely literary grounds (I think it does, but I'm open to discussion) but his legacy is far more important and enduring.

Not bad for a guy who died at 40 in abject poverty and near obscurity.

10/01/2018

Edgar and Willard

Readers of this blog know my péché mignon is to go against the grain and taking stances that are deliberately provocative, counterintuitive or both. You had a prime exemple with my last post in which I bluntly attacked that founding element of the crime fiction genre, series characters. You won't be surprised then that one of my most recent exploits was a post on the Golden Age Detection FB in which I appeared to defend Van Dine's infamous rules, particularly the much-maligned #3 (no love stories) and #16 (no "literary flourishes") I expected some reaction and lots of reaction I had, most of it negative. Even hardcore GA fans love their romantic suplots and atmospheric touches it appears.

Not that I blame them. My support for Van Dine was mostly tongue-in-cheek, as most of the writers and books I admire wouldn't pass muster if his rules were to be strictly enforced. Still, I think they are not quite without merit either, and certainly in line with the thinking of the "founder" of the genre, Edgar Allan Poe himself.

While Poe nowadays is primarily known for his fiction and poetry, he was also famous in his lifetime for his literary criticism. Famous but not popular, at least with his colleagues as he eviscerated most of them for their slopping writing, inordinate length and, crucially to him, poor plotting. Poe was probably the first writer to realize that art is not only a matter of inspiration and emotion but of efficiency. He famously delineated his doctrine in his review of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales:

A skilful literary artist has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents–he then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect. If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step. In the whole composition there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design. And by such means, with such care and skill, a picture is at length painted which leaves in the mind of him who contemplates it with a kindred art, a sense of the fullest satisfaction. The idea of the tale has been presented unblemished, because undisturbed; and this is an end unattainable by the novel. Undue brevity is just as exceptionable here as in the poem; but undue length is yet more to be avoided.

This approach ran contrary to the then-predominant Romantic ideas about creation and was received with skepticism or open contempt by those who thought Art and the Sublime couldn't be reduced to a simple matter of mechanics. To others, however, it was a good lesson and one they strove to follow. What connects Poe to Van Dine, for all their many differences, is this willingness to root out everything extraneous to the effect they sought to achieve, fooling the reader in Van Dine's case. We are fortunate that their respective followers didn't take their advice too literally for the genre wouldn't have gone very far had all detective stories (not novels; Poe was no fan of those) been in the same mould as the Dupin trilogy. On the other hand, we would have been spared much of the phonebook-sized rambling "crime fiction" that tops the bestsellers lists and wins plaudits and awards these days.

My position is a median one. I don't want my mysteries to be sudoku games in (flat) prose, focused on the puzzle at the exclusion of everything else - but neither do I want to be bludgeoned with pages of furniture description, personal relationships and angst whose sole raisons d'être are a higher page count and enhancing the writer's reputation with the Literati. Great crime fiction of the past was both economic and focused, which didn't keep it from being strong on atmosphere and character when the writer saw fit. Just because a book is longer and offers "literary value" doesn't mean that it's good. So maybe Van Dine's rules are still worth thinking over, if not being closely obeyed, after all.

Further reading:

An "interview" of Edgar Allan Poe on his 200th birthday.

Noah Stewart on Van Dine's rules

Not that I blame them. My support for Van Dine was mostly tongue-in-cheek, as most of the writers and books I admire wouldn't pass muster if his rules were to be strictly enforced. Still, I think they are not quite without merit either, and certainly in line with the thinking of the "founder" of the genre, Edgar Allan Poe himself.

While Poe nowadays is primarily known for his fiction and poetry, he was also famous in his lifetime for his literary criticism. Famous but not popular, at least with his colleagues as he eviscerated most of them for their slopping writing, inordinate length and, crucially to him, poor plotting. Poe was probably the first writer to realize that art is not only a matter of inspiration and emotion but of efficiency. He famously delineated his doctrine in his review of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales:

A skilful literary artist has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents–he then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect. If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step. In the whole composition there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design. And by such means, with such care and skill, a picture is at length painted which leaves in the mind of him who contemplates it with a kindred art, a sense of the fullest satisfaction. The idea of the tale has been presented unblemished, because undisturbed; and this is an end unattainable by the novel. Undue brevity is just as exceptionable here as in the poem; but undue length is yet more to be avoided.

This approach ran contrary to the then-predominant Romantic ideas about creation and was received with skepticism or open contempt by those who thought Art and the Sublime couldn't be reduced to a simple matter of mechanics. To others, however, it was a good lesson and one they strove to follow. What connects Poe to Van Dine, for all their many differences, is this willingness to root out everything extraneous to the effect they sought to achieve, fooling the reader in Van Dine's case. We are fortunate that their respective followers didn't take their advice too literally for the genre wouldn't have gone very far had all detective stories (not novels; Poe was no fan of those) been in the same mould as the Dupin trilogy. On the other hand, we would have been spared much of the phonebook-sized rambling "crime fiction" that tops the bestsellers lists and wins plaudits and awards these days.

My position is a median one. I don't want my mysteries to be sudoku games in (flat) prose, focused on the puzzle at the exclusion of everything else - but neither do I want to be bludgeoned with pages of furniture description, personal relationships and angst whose sole raisons d'être are a higher page count and enhancing the writer's reputation with the Literati. Great crime fiction of the past was both economic and focused, which didn't keep it from being strong on atmosphere and character when the writer saw fit. Just because a book is longer and offers "literary value" doesn't mean that it's good. So maybe Van Dine's rules are still worth thinking over, if not being closely obeyed, after all.

Further reading:

An "interview" of Edgar Allan Poe on his 200th birthday.

Noah Stewart on Van Dine's rules

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)

Groups and Forums

Great Sites

- A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection

- All About Agatha Christie

- Arthur Morrison

- Bill Crider's Pop Culture Magazine

- Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind

- Crime & Mystery Fiction Database

- Crime Time Magazine

- Ellery Queen, A Website on Deduction

- Grobius Shortling

- Jack Ritchie: An Appreciation and Bibliography

- Mysterical-E

- Tangled Web UK

- The Arthur Porges Fan Site

- The Avram Davidson Website

- The Ellen Wood Website

- The Grandest Game in the World

- The Gumshoe Site

- The John Dickson Carr Collector

- The Mystery Place

- The Strand Magazine

- The Thrilling Detective

- The Unofficial Robert Bloch Website

- The Wilkie Collins Website

- Trash Fiction

- Who Dunnit